How the World Breaks: Schizophrenia and the Science of Experience.

Phenomenology is the philosophical investigation of lived, first-person experience. It separates itself from analytic philosophy, clinical psychiatry, and cognitive science, which often rely on objective data to drive a point across. Phenomenology operates within the subjective, offering a direct analysis of how subjects live and experience the world. This provides access to the meaning-structure of mental life — a crucial part of understanding mental health — showing what happens when those structures collapse, as in schizophrenia. Unlike clinical psychiatry, it reveals how the world is lived as broken. This essay will outline the phenomenological method, contrast it with psychiatric approaches, and illustrate its insights through schizophrenia.

The Phenomenological Method

The founder of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl, describes it as the “science of experience” — not of the external world, but of how that world appears to subjective consciousness. All consciousness is structured; it is always consciousness of “something.” This is his notion of intentionality. Husserl’s method of epoché, often called “bracketing,” suspends our natural assumptions about the external world to focus on how things appear within experience. Rather than asking whether the world is as it seems, phenomenology studies how it seems, and what structures make that possible.

This becomes crucial in understanding mental illness, where the ordinary givenness of the world is disturbed at its roots. In Feelings of Being, Ratcliffe describes depression not as a mood shift but as an existential breakdown — a collapse of the world itself. Phenomenology reveals how this breakdown is lived, deepening our understanding of psychiatric suffering. Similarly, Merleau-Ponty argued that perception is always embodied; we do not observe the world from a detached cerebral position, but from a bodily standpoint within it.

Phenomenology offers tools for analysing embodied cognition, revealing not things as they are, but as they appear to a subject embedded in the world — essential when that world is disturbed.

Schizophrenia and the Breakdown of the Self

Psychologist Louis Sass has long argued that schizophrenia should be seen as a form of hyper-consciousness rather than a deficit. He describes it as a breakdown of the minimal self. This becomes clear in how individuals with schizophrenia experience themselves: rather than acting spontaneously, they become spectators to their behaviour, watching, observing, doubting the authenticity of their thoughts and voices. This hyper-awareness, which most of us do not possess, is paired with a fading of the immediate “I-ness” of experience.

Dan Zahavi calls this loss “self-affection” — the basic sense that one’s thoughts are truly one’s own begins to erode. Phenomenological analysis shows this isn’t just a disruption in thought or perception, but a foundational transformation in experience itself.

Psychiatrist and phenomenologist Wolfgang Blankenburg describes schizophrenia as a “loss of natural self-evidence.” By this, he means the intuitive framework through which we inhabit the world — our grasp of emotion, social norms, and everyday meaning — begins to dissolve. What once felt obvious now feels alien. In early schizophrenia, it isn’t just that someone misreads cues — the very sense of there being a shared world starts to collapse.

Imagined reflection from someone in this early phase:

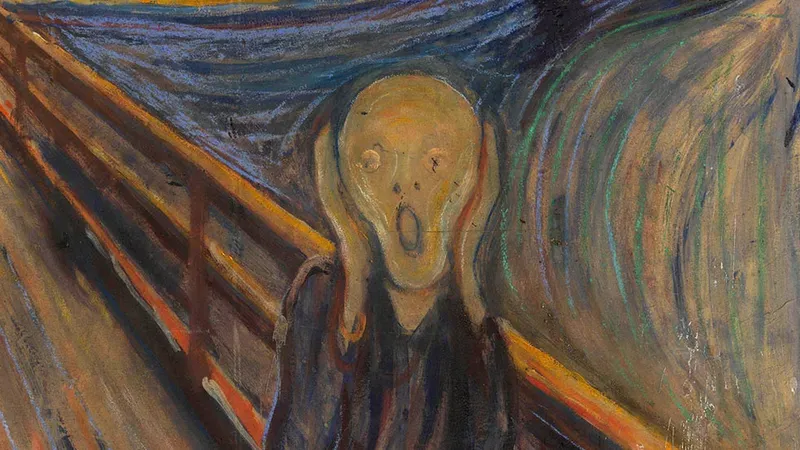

“The smiles people give me feel hollow, without warmth or meaning. The rooms I enter no longer feel like real places. The conversations I have with colleagues and friends feel staged, full of hidden signals. It’s like they’re trying to tell me something. I feel like the world is running on a script only I can read. Like I’m the only real person.”

This is not yet delusion, but it’s the soil from which delusion grows: a loss of orientation in a world that becomes estranged.

Diagnosis vs. Experience

Clinical models often interpret these experiences as “hallucinations,” but phenomenology reveals them as world-distortions — disruptions in how time, meaning, and agency are structured. It’s not just what the person believes that changes, but how the world itself is given. Only phenomenology captures this inner logic — how madness is lived from within.

What phenomenology achieves is an enrichment of clinical psychiatry, restoring its human core and grounding it in understanding, not just diagnosis. This is not about rejecting neuroscience but about complementing it with insights into structures of experience that no scan or checklist can reveal.

Phenomenology shows how the world can be altered in its very givenness — how reality unravels for a suffering subject. Instead of reducing schizophrenia to delusions or faulty cognition, it reveals a fractured way of being.

Conclusion: Entering the Ruins

Clinically, this helps psychiatrists understand patients more clearly. Philosophically, it opens deeper questions about the fragility of subjectivity, the limits of reason, and what makes a shared world possible.

Phenomenology offers a lens that cognitive science cannot — one that reaches into the heart of lived experience. In schizophrenia, what breaks down is not merely cognitive; it is ontological. The self dissolves, and the world distorts. Phenomenology describes this from within, offering tools to understand what these conditions mean.

To understand someone in crisis, we must go beyond diagnosis. We must be willing to enter a world that has lost coherence — and trace, with care, the ruins of meaning left behind.