If Happiness Is All That Matters, Should We Destroy the World?

If morality is just a numbers game, should Earth be sacrificed for the greater good?

Utilitarianism argues that the best action is one that maximises happiness—but what happens when this reasoning is applied on a cosmic scale? Utilitarianism reduces ethics to rational calculus—an idea first formulated by Bentham (1789)—which has sparked disagreement and debate for centuries. John Rawls famously critiques this logic, arguing that utilitarianism fails because it treats individuals as vessels for happiness, wholly ignoring their own lives, interests, and moral worth. This is known as the Separateness of Persons objection.

To illustrate this argument, I introduce a thought experiment: The Cosmic Census—utilitarianism stretched to its logical conclusion, leading to an absurd, yet eerily plausible, outcome. This essay will argue that Rawls’ separateness principle effectively dismantles utilitarianism. The Cosmic Census aims to reveal that when utilitarian logic is taken to its limit, it can justify extreme and morally indefensible sacrifices in the name of the greater good—thus proving Rawls’ critique correct.

Utilitarianism is frequently criticised for reducing moral judgment to cold, mathematical reasoning that overlooks individual worth. The Separateness of Persons objection is perhaps the most forceful counter. It argues that utilitarianism treats society as a single moral agent—where only the total sum of happiness matters, not who experiences it. But people live separate lives, with distinct goals, relationships, histories, and emotions.

Rawls (1971) contends that every person possesses an inviolability grounded in justice that cannot be overridden by appeals to the collective good. To sacrifice one person to benefit another is like cutting off someone’s leg to help another run faster. It assumes that all interests can be merged into one unified moral entity—but they cannot. The interests of a man in Alexandria do not align with those of someone in Exeter. Utilitarianism ignores this basic truth. It assumes we are morally bound to maximise others’ well-being simply because we are all human, while disregarding that we do not owe each other our lives.

Rawls’ critique becomes even more striking when applied on a cosmic scale. Consider the following thought experiment: The Cosmic Census. Imagine an alien civilisation from the planet Hedon-7—the most technologically advanced in the universe. These aliens are strict utilitarians, followers of the ancient teachings of Xorgus Benthamoid (whose ideas mirror human utilitarianism). With advanced technology, they can survey the happiness of every sentient being in the cosmos—over 38 million planets and 1.6 quadrillion conscious lives.

They establish the Collective Interest Administration (C.I.A.), tasked with maintaining a minimum universal happiness rate of 50.1%. Through their census, they discover that Earth is profoundly unhappy, lowering the cosmic average to 49.6%. By destroying Earth, the happiness rate would increase to 50.1%, thus fulfilling their moral directive. The logic is clear: if morality is about maximising happiness, and if this principle applies universally to all sentient life, Earth should be destroyed.

As Mill wrote, “Actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness” (1861, p. 9). The utilitarian ethos does not limit itself to humans. This is not mere hyperbole—it is the inevitable conclusion of utilitarian reasoning. If Bentham and Mill are right, Earth’s extermination is not just acceptable—it is required.

This isn’t the first time such concerns have been raised. Robert Nozick (1974) introduced the concept of a Utility Monster—a being capable of such immense happiness that everyone else should sacrifice themselves to feed it. The Cosmic Census inverts this: Earth becomes a Negative Utility Monster—a world whose suffering justifies its erasure.

Both cases reveal the same fatal flaw: utilitarianism reduces people to data points in a cost-benefit spreadsheet. It treats persons not as ends in themselves, but as variables to be optimised. Rawls was right: moral worth cannot be captured by aggregate happiness.

Now reverse the scenario. Earth joins the C.I.A. as an evaluator. The next census finds that Planet XGY7 is a net-negative world. Should Earth vote to vaporise it? If we follow utilitarian logic, the answer is yes.

Bernard Williams (1973) illustrates a similar problem in his thought experiment Jim and the Indians. Jim must choose between killing one innocent man or letting twenty be executed. Utilitarianism says: kill the one. But Williams, like Rawls, sees this as a violation of moral integrity. Similarly, if humanity values dignity and justice, it cannot endorse mass death—no matter the numbers.

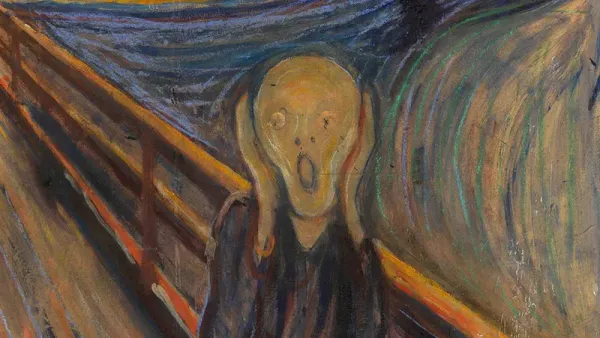

The Cosmic Census reveals that the Separateness of Persons is not just a local principle—it is universal. Whether it applies to humans or aliens, Earth or Hedon-7, no moral system should justify planetary extermination. To do so is to abandon justice altogether.

Despite its intuitive appeal, utilitarianism collapses under the weight of the Separateness of Persons objection. If morality is simply a matter of maximising happiness, individual rights become irrelevant—and catastrophic sacrifices are inevitable. The Cosmic Census, though absurd in form, reveals the logical end of utilitarian thinking.

Any moral system that can justify the destruction of an entire planet for a 0.5% increase in total happiness is not just flawed—it is dangerous. Rawls’ critique isn’t merely about hypothetical extremes. It exposes the core failing of utilitarianism: reducing morality to numbers and forgetting the dignity of persons.

Morality should not be a spreadsheet. People are not numbers. The moment we let arithmetic dictate who lives and dies, we abandon justice itself.

Bibliography

Bentham, J., 1789. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. London: Oxford University Press.

Mill, J.S., 1863. Utilitarianism. London: Parker, Son, and Bourn.

Nozick, R., 1974. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. New York: Basic Books.

Rawls, J., 1971. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Williams, B., 1973. Utilitarianism: For and Against. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Daniels, N., 1993. ‘Rationing Fairly: Programmes, Problems, and Principles.’ Journal of Medical Ethics, 19(1), pp.1-15.

Singer, P., 1993. ‘Practical Ethics and Animal Rights.’ Ethics & International Affairs, 7(1), pp.19-31.