The Man Who Folds His Shirt: A Manifesto on Aesthetic Virtue in an Age of Collapse

Epigraph

Written in one fevered four-hour marathon on a dry summer night, July 10th, 2025, in Hertfordshire — after three months of philosophical pacing, playlist-making, existential spiralling, and precisely zero shirtless club nights.

This essay is the result of an obsession: with rhythm, with presence, with form. It began as a stray line scribbled (admittedly) during a moment of reflection in the washroom — “what beauty is left when God dies?” — and ended as the clearest thing I’ve ever written. I’ve thought about this work on trains, in cafés, between gym sets, and mid-speech.

I wrote this to remember who I am. I wrote it for those who refuse to disappear. And I wrote it because, somewhere along the way, folding a shirt started to feel like a philosophical act.

To anyone reading: thank you for your time, your mind, and your attention.

I hope this finds you in rhythm.

1. The Man Who Folds His Shirt

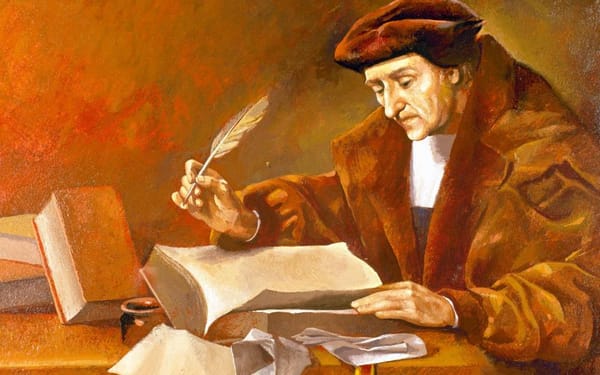

On a cool, rainy October evening, I’m sitting at my desk at the University. Pen and notebook in hand, I sketch out my philosophical musings, a steaming cup of coffee resting beside me. The soft lulls of Chet Baker play on the record player in the corner of the room, and I feel the gentle touch of my Egyptian cotton shirt against my writing hand — freshly pressed an hour ago, for no one in particular.

In the background, I hear the storm of students rushing out for that night’s club special — a night of drinking, noise, and hedonism awaits. I begin to compare myself: why do I find pleasure in the slow, finer things, rather than in the fast-paced neon lights and the burn of one jaeger bomb after another clawing down the back of my throat?

I’ve often wondered what draws me so deeply to these rituals. The suit pressed for no one. The horn of cool jazz drifting through the silence. The slow pour of coffee. All of it feels like a language — not of luxury, but of resistance.

Is it simply taste? Or is there something more sacred about choosing beauty in a world that rushes past it?

For a long time, I’ve found myself drawn to a certain kind of man. Not the richest, not the most handsome — but the most composed. Someone who lives so authentically, so beautifully, that his existence — as a certain philosopher might put it — is inherently an act of rebellion. I cannot help but believe that, in an age of collapse, there is something quietly defiant about the man who still folds his pocket square

2. On judgement, collapse, and misunderstandings.

Nowadays, there is something vaguely suspicious — even comical — about a person who dresses well without purpose. To speak eloquently is labelled pretension. To drink slowly, to move deliberately, is to be called decadent. To care is to be called performative. To be passionate is to be called cringe.

In an age of irony and late-stage capitalism, we have replaced ritual and form with speed, attention, and consumption. As Byung-Chul Han — a personal favourite of mine — writes in The Disappearance of Ritual, ours is a time allergic to ceremony, allergic to slowness (Han, 2020, p. 2). The old gestures of form — pressing one’s shirt, saying thank you slowly, speaking with purpose — have been flattened into kitsch or commodified into aesthetics. They’ve lost their “aura,” as Walter Benjamin might say (Benjamin, 2008, p. 10).

Many assumptions are made about the man who walks deliberately, who orders wine instead of a vodka mixer, who speaks in rhythm and full sentences. He is quickly diagnosed: nostalgic, elitist, insecure, out of touch.

“Why try so hard?” is the chorus repeated around anyone who dares to live authentically — who refuses the ease of collapse. In our time, caring is treated as a kind of pathology, a social aberration to be corrected, so that we may all fit neatly into the same box.

But these readings are, I believe, criminally mistaken. What I aim to do — how I choose to represent myself — is neither pretence, nor escapism, nor regression. The way of life I preach — attention to form, to grace, to beauty, to knowledge — is not vanity. It is a response. A stance. An ethic. One of rebellion — a metaphysical rebellion, as Camus might put it — against the conditions placed upon us as creatures of society (The Rebel, 1951, p. 29). To live truly, and beautifully, in accordance with one’s inner presence.

It is not that I romanticise the past — only that I refuse to surrender what I hold sacred in the name of recognition and acceptance.

3. Of Culture, Collapse, and the Death of Form.

We live in a time best summarised as one of cultural exhaustion. The lines between consumption and culture have flattened — resulting in a global collapse of meaning, ritual, and elegance. In places like American Samoa, indigenous foodways, music, and rituals have been replaced with commodified imports: junk food, neon branding, and the spiritual imperialism of the dollar. The result? The highest obesity rates on Earth (World Health Organization, 2017).

We speak of culture in the plural — pop culture, internet culture — but rarely, if ever, as a mode of being. We have not merely lost content; we have lost form — the shape that gives objects metaphysical meaning.

Where rituals once shaped identity, ours are now curated on screens, in echo chambers, or as Han would say — “isolated acts of stimulation” (Han, 2020, p. 5). Where art once pointed to the sublime, it now signals merely toward attention. Culture, in the old sense of the term, was not entertainment. It was cultivation.

Let me be clear: by culture, I do not mean sociology or cultural critique. It is metaphysics lived through ritual — a central principle in my metaphysical theory of the sublime. It is the web of practices by which a people come to encounter beauty, death, virtue, and — most beautifully — each other.

It is a vital mistake to assume that, despite its claims to universality, philosophy is cultureless. In fact, I argue that culture is inherent to philosophy. And when culture collapses, philosophy becomes disembodied. It malforms into abstraction without ritual, logic without rhythm — thought without a body to speak through.

For all its universal claims, philosophy is always born from culture: from its stories, its silences, its forms of address, its gestures and conventions. Greco-Roman philosophy was shaped by the theatre and the agora — it lived under open skies, in sandals, in song, in tireless debates under the Mediterranean sun. Confucian thought emerged from ritual propriety, familial piety, the bow, the tea ceremony — its ethics were gestures long before they were texts. Islamic metaphysics were woven into the rhythms of the Qur’an, the art of calligraphy, the rigor of jurisprudence, the sacred geometry of mosques — architectural symmetry was not decorative, nor merely mathematical, but metaphysical. Even European modernity, for all its pretensions to cold rationalism, was born of Latin, cathedral ceilings, and the structure of scholastic prayer.

To forget this is not to liberate thought. It is to gut it. Severed from the soil in which it once grew, philosophy becomes procedural, dry, performative — a mouth desperate to speak with its tongue cut off.

This disembodiment now reaches its most extreme form in the divide between analytic and continental philosophy. In one camp: clarity reduced to computation — logic and rigour stripped of its soul; language treated as code. In the other: depth reduced to gesture — affect without discipline, metaphor without grounding. Both sides fail to touch the world, because neither side can fully dwell within it.

Both traditions, in their own ways, suffer the same crisis: the disappearance of form. And it is form — not content — that philosophy cannot survive without.

These examples are precisely why I do not treat, or view elegance as decorative, but rather – essential. In a cultureless world, elegance is not excess — it is now memory. Form, in the purest sense, is the last vessel that still manages to carry meaning across time.

It is my wager that what I dub — “aesthetic virtue” — the disciplined return to form, pose, eloquence, grace, and ritual is not a retreat from philosophy, but a return to the quintessential philosopher. When metaphysics becomes ungrounded, when logic becomes bodiless, it is in attention to the smallest details — the suit tailored to perfection, the coffee made and drank with care, the silence chosen in place of ego-building noise — that we begin to live truthfully once more.

What now follows is not an argument, but rather, a mode of being expressed in words. Not a defence, but a demonstration. One of a life lived carefully — not in fear, but in terrifyingly lucid fidelity.

This is my attempt to rebuild meaning from the inside out — through presence, through attention, through beauty that refuses to be meaningless

4. Aesthetic Virtue: The Ethic of Poise

What I believe in — and what I hope to successfully articulate here — is the previously coined term: aesthetic virtue. It is important to note, dearest reader, that the word aesthetic is not used here in its modern, hollow sense. It does not represent mere taste, lifestyle, or luxury, but rather — the disciplined choice to live beautifully. Not for display, but for alignment.

It is the ethic of form: of dressing, speaking, drinking, writing, thinking, and walking with poise, when nothing and no one demands you to do so. It is the quiet refusal to surrender in the wake of collapse. A wager not rooted in grand abstract systems, but in simple gestures, done well.

The pocket square folded perfectly each morning is akin to Wittgenstein’s insistence that “ethics and aesthetics are one” (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, §6.421, 1921). It is form revealing the moral orientation of a life — not through argument, but through poise.

Where ritual disappears, I restore it with rhythm. Where culture fades, I reconstitute it in silk and in silence. Aesthetic virtue must not be mistaken for performance but recognised for what it is: a metaphysical rebellion against the human condition (Albert Camus, The Rebel, p. 29, 1951).

Aesthetic virtue does not emerge solely from my mind; it stands within a long tradition of ethical philosophy in which character is formed not merely by rules and beliefs, but through repetition, ritual, and care. In this sense, it is not an invention, nor a new kind of morality, but a revival of something older than modernity: the shaping of the soul through form and personality.

In Ancient Greece, Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics presents virtue (arete) not as an abstract ideal, but as a cultivated state of character: “we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts” (Nicomachean Ethics, II.1, 1103a15). Virtue, for Aristotle, is not knowledge or conscious repetition, refined through action, and ultimately inscribed into the self.

This theme echoes in Confucian philosophy. Centuries earlier, Confucius taught that ritual (li) was the foundation of ethical life. In the Analects, he writes: “If a man is not humane, what has he to do with ritual?” (Analects, 3.3). Like me, Confucius saw the everyday gesture — the bow, the tea ceremony, the funeral rite — not as ornament, but as ethics lived through form.

Aesthetic virtue belongs to this lineage. It is a contemporary answer to an ancient question: how shall I live, when the world no longer demands virtue? To walk with poise, to speak with clarity, to drink with grace — these are not aesthetic flourishes, but ethical forms. Forms that, like Aristotle’s habits or Confucian rituals, shape the human person from the outside in.

To live with aesthetic virtue is not simply to act with care, but to persist in care despite misunderstanding. It is to be seen as affected, performative, or insincere — even when nothing could be further from the truth.

But what does aesthetic virtue look like, in practice?

It lies in sharpening your fountain pens before lectures — not because anyone will notice, but because words deserve precision.

In correcting your posture before making a phone call.

In pausing, briefly, to smooth the napkin at a café table before opening your book.

In returning a library book and placing a note inside: a line of gratitude, or a quote you found meaningful.

These acts are not done to perform a persona, or to impress. They are not performances of elegance or grace. They are rituals of resistance — quiet refusals to decay inwardly in a world that demands speed, irony, and collapse.

These actions are rarely congratulated and often mocked. You may be called a relic, a contradiction, an overthinker. You will hear “you’re too much” far more often than “you’re right.” But you continue — not because it will change the world, or redeem the future, but because it is the only way to remain true, and alive, among the dead.

This is the true nature of aesthetic virtue: not to decorate existence, but to hold it together. Not to charm others — but to remain recognisable to yourself, when you meet your own gaze in the mirror.

5. The Geometry of Care

I have regularly invoked the term “form” throughout this essay, without strict definition—as I’m sure the philosophically apt amongst you have now noticed, but this was not without intention, as any good philosopher should do, I shall proceed to provide the shape of meaning henceforth.

In the modern imagination, “form” is regularly dismissed as superficial, as the aesthetic packaging of something else that’s more essential, beneath the cover. It is mistaken merely for surface, ornament, a distraction from substance. But this perception betrays a deeper philosophical blindness. Form is not surface it is structure. It is the architecture of intelligibility itself, essential, the very condition by which meaning can be made, recognised, preserved. A sentence, a silence, a gesture, a gaze: each holds power only insofar as it has shape. Without form, experience collapses into mere noise—raw, unsorted, uninhabitable, just as syntax gives structure to speech or rhythm gives coherence to music, form gives orientation to life. It does not conceal meaning but makes it possible in the first place.

Take, for example, the choice to write with a fountain pen. This is not merely a matter of style. It is a commitment to form — to the idea that meaning deserves shape. The precision of the nib, the resistance of the paper, the slowness of the stroke — these are not luxuries, but constraints. And within these constraints, a profound phenomenon occurs care becomes visible. Meaning, far from being an ethereal abstraction, must take shape in the world to exist. As Wittgenstein observed, “Form is the possibility of structure” (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 2.033). Just as grammar gives rhythm to thought, or melody gives coherence to sound, the form of an act — how it is done — gives it ethical legibility. Merleau-Ponty reminds us that perception is always already structured; we encounter not raw data, but gestalts — configurations of sense (Phenomenology of Perception, 1945). To act without form, then, is not to be more authentic. It is to be illegible. Every gesture, if it is to truly express character and endure, must take form — whether a bow, a phrase, a speech, or a pen stroke. Form is what holds intention long enough for it to be received. A love letter written in haste, on the back of a receipt, in broken phrases, does not express deeper sincerity — it reveals a fundamental lack of care. One written in calligraphy, on vellum, demonstrates not only devotion to the one loved, but to love itself. The form does not decorate meaning. It upholds it.

Despite these definitions and perspectives on form, my beliefs are only relevant insofar as they are unique. And they are — because we are living through an era of the formless. Not merely cultural, but moral, linguistic, interpersonal. In all areas of intellectualism, rhetoric, and daily life, form has been eroded.

What are the consequences of this, you ask, dear reader? Without form, the intention behind an act dissolves long before it can register. A suit pressed for no one is an act of quiet defiance — but what happens when no one presses it at all? The shirt folded without witness holds a special kind of meaning; it says: I care, even unseen. But when the gesture disappears entirely — not out of rebellion, but erosion — then intention ceases to have a vessel. What once served as resistance, as statement, becomes absence. What once signified dignity… becomes silence.

As Han warns, without continuity, without ritual, we begin to lose memory itself — life becomes a series of disconnected stimulations rather than a narrative of interconnected meaning (Han, 2020, p. 5). Benjamin, too, foresaw this: when art is detached from its origin, its presence, its method and its slowness, it loses its aura — its capacity to signify something beyond circulation or economic gain (Benjamin, 2008, p. 10).

This effect ripples through modern life. In public discourse: irony has replaced sincerity; sarcasm protects the ego; language is hedged with disclaimers, trigger warnings, hashtags, and emojis — all compensating for our fear of being misunderstood or hated. In personal ritual: meals are eaten while walking, culinary elegance is replaced by convenience-store fuel designed to keep the machine running. Texts replace farewells. TikTok’s replace love letters. Group gatherings collapse from conversation into silent, mutual scrolling.

This loss is not merely cultural. As already established, form — and the lack thereof — is metaphysical. Without form, our actions cannot carry intention. Without intention, we do not communicate. We react.

Ethics loses legibility. Art loses permanence. Love loses expression. Philosophy loses its seat at the table.

When form dies, so too does our ability to be known.

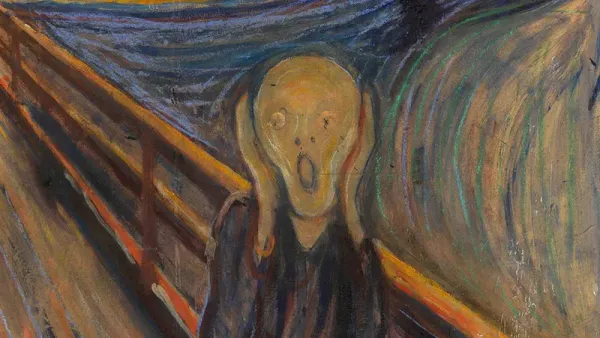

And that, I believe, is the most harrowing crisis of the modern day:

The loss of beauty.

6. What Beauty is Left, When God Dies?

Let us now, finally, confront the silent axiom beneath all of this. If we apply the clear Camusian framework I have undertaken in this essay, and throughout my work, both in oration and in literature. If there is no God, no afterlife, no cosmic justice or retribution—if the universe is, as Camus once put it, “unreasonable silence”—then what exactly justifies this kind of life, one in pursuit of beauty? Why choose to write with a fountain pen when the world is burning? Why bother to press a shirt no one will compliment? Fold a napkin for no one to witness? Speak with grace when not a single ear rewards sincerity or authenticity? When nothing greater watches, and no eternal ledger of your good deeds versus your sins are recorded, why persist in beauty?

This is where, admittedly, most of my frameworks face their fiercest challenges. In a disenchanted world, where metaphysical guarantees have evaporated, elegance can now appear wholly irrationally—dare I invoke the term, absurd. There is no divine judge to praise your posture, no cosmic scale to balance the dignity of your small gestures in contrast to those who live boorishly. Beauty, in this light, seems like a relic—charming, perhaps, lovely to write or dream about, but fundamentally obsolete.

But this too serves to be a grave misreading. Beauty is not a consolation prize for those too weak for the truth. It is the discipline of those who know the truth, who have stared into the abyss long enough for it to stare back into them and choose, still, to live life as if it were worthy of form. As Nietzsche writes in The Birth of Tragedy, “it is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified” (Nietzsche, 1872/1999, p. 52). Beauty in this light now, does not serve to promise beauty. It creates it—in defiance of its innate absence, in a Godless world.

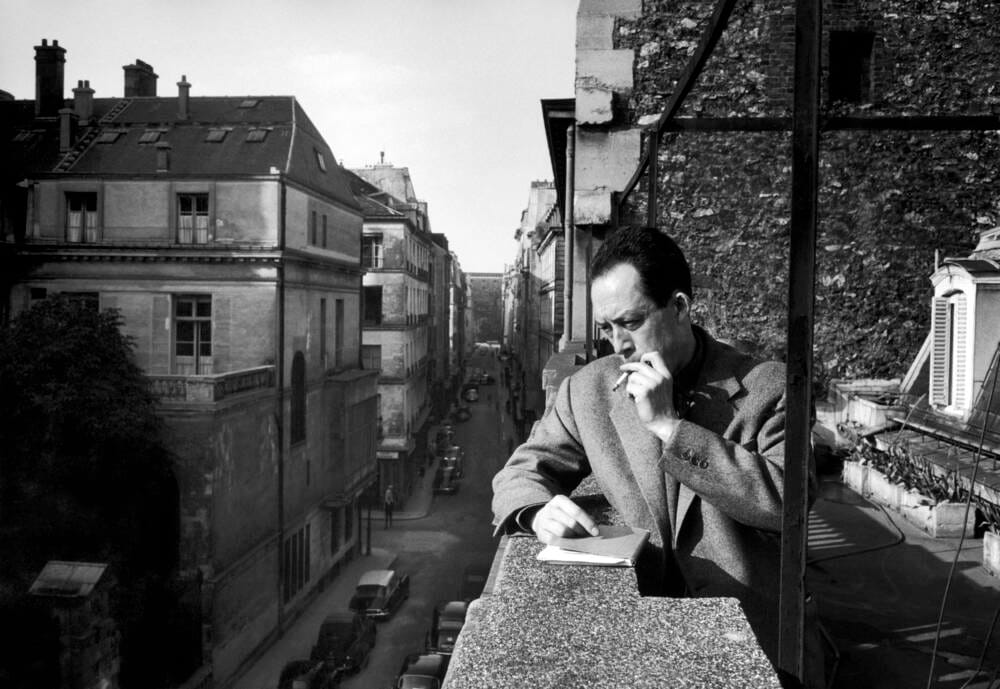

To act with grace in a graceless world is not self-delusion, nor is it a futile dance against the absurd. It is clarity born into flesh. Camus dubbed this metaphysical rebellion: the refusal to succumb to the absurd, the decision to live coherently amidst an incoherent world (Camus, 1951, p.29). The rebel does not destroy—he demands form. If Sisyphus, the absurd hero, were granted the opportunity to drink coffee before pushing the boulder up the mountain, he would, undoubtedly, drink it slowly, and fold the napkin up neatly as he leaves.

This should not be misunderstood as hedonism, nor aestheticism, nor escapism. It is not delight, or pleasure, but dignity. Not style, but structure. To live with aesthetic virtue is to lucidity carry the weight of meaning on one’s back—to choose form not because it is seen or lauded, but because without it, you would disappear. To achieve aesthetic virtue, you must constantly remind yourself of the apathy of the universe, and all the while acknowledging that there is no one else to impress, there is only the self you must continue to recognise, and to impress yourself every morning you are fortunate enough to wake up once more.

For most of human history, beauty was understood as teleological—it pointed beyond itself, to eternity. Plato in his Symposium, Diotima describes beauty as the ladder the soul ascends, moving from the body to the mind, from desire to truth, until it reaches the eternal Form of the Good (210a-212b). In Augustine’s Confessions, beauty now becomes the echo of divinity itself— “ever ancient, ever new”—a shimmering sign of the God who once created it (Book X). To live beauty was to live toward something—to let your love of form lead you home, to the creator.

But now that we have established there is no home to return to, no Form of the Good to aspire to, as the voice of God now falls definitively silent. What remains still?

In a disenchanted world, beauty no longer serves to point beyond. It does not promise, nor does it redeem. It longer pulses as a symbol of the divine—it is the last gesture of the human. I do not fold my shirt in the morning to be seen by heaven. I do not write with a fountain pen in a beautiful café because it leads me closer to divine retribution. I do it because it keeps me close to myself.

Albert Camus once wrote, “There is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn” (The Myth of Sisyphus, 1942/1991, p. 121). But where I differ from who is admittedly my greatest inspiration, is that I do not meet absurdity with scorn. I choose to meet it with style. With clarity. A voice sharpened against collapse. Mine is not the rebellion of fire and change—it is the rebellion of form, of beauty.

To live with aesthetic virtue is to live without illusions—and still choose beauty. I do not drink Bordeaux or tailor my blazers to be saved. I do it so that I remind myself, constantly, against all odds, I am alive. These rituals are not acts of faith, but ones of fidelity—not to God, but to consciousness. To the unbearable, incredible privilege of presence.

Søren Kierkegaard once spoke of the “knight of faith”—a solitary figure who walks toward the unknown, not with despair, but with grace! (Fear and Trembling, 1843/1983). I am no knight. I do not demand faith. I only demand form. A polished shoe. A smooth lapel. A quiet refusal to disappear. My religion is not mere salvation. It is attention.

This is my wager: not that I will be rewarded for living beautifully—but that I will remain visible to myself even when the heavens stay eerily silent. When the stars no longer sing, the act of folding one’s shirt is not trivial. It is the final rite of the soul.

And yet, despite the poetic closing written above, we must venture to go further. It is certainly enough to say beauty now persists despite the absurd, but to create a system—we must also say why. In a world where transcendence has withdrawn, where the sacred no longer descends from on high, it is now up to us to raise it from below. Beauty becomes sacred not because it is commanded—but because we return to it. This is what Albert Borgmann called “Focal Practices”: those small, deliberate rituals—setting the table, sharpening a knife, pouring wine—that draws us back into being, anchoring life during technological distraction (Borgmann, 1984, p.186). These are not nostalgic gestures, they are inherently metaphysical acts.

Heidegger too foresaw this need. Even in a disenchanted, ruined world, he wrote “poetically man dwells”, not as escapism, but as our last responsibility; to give form to the formless, to let the world be gathered, and allow it to be named again. (Heidegger, 1971, p.215). To dwell poetically is not to believe in Gods—but to live as if the world were still worthy of reverence. And reverence, here, is expressed through form. Through ritual. Through care.

The jacket hung with intention. The coffee stirred without urgency and sipped with slow, methodical enjoyment. The choice to speak eloquently over slang, in poetics over insults. These are not empty aesthetics. But declarations of presence. Devotion, and refusal. Now, Aesthetic Virtue is not just a personal style. It is a metaphysical integrity. Nietzsche once wrote in The Gay Science, that “Style ought to prove that one believes in an idea; not only that one thinks it, but now also feels it.” (Nietzsche, 1882/1974, §290). And I would go further: style is not belief made visible — it is belief made liveable.

I do not claim that beauty will save us. I do not claim it will grant us peace, or meaning, or permanence. I claim only this: that it will allow us to remain recognisable to ourselves, when all else collapses. Camus once wrote, “To live is to keep the absurd alive” (Camus, 1942/1991, p. 60). I would add — to live beautifully is to keep dignity intact, even when abandoned. That is all I offer. Not salvation. Just the shape of a life that does not vanish.

Conclusion: The Final Gesture

And so, in the end, what is offered here is not a manifesto, nor a doctrine—but a life lived in fidelity to form.

Not because it is fashionable. Not because it is noticed. But because, when all else vanishes—God, tradition, culture, transcendence—what remains is how one enters a room. How one sets a table. How one speaks when no one is listening.

This is not nostalgia, nor is it dreaming. It is, in the truest sense possible, rebellion.

Aesthetic virtue is not performance. It is a daily decision to meet incoherence with coherence. To choose grace when there is no audience to laud you. To walk as if dignity still mattered.

Even if the lights go out, the ritual remains.

And I, for one, will keep folding my shirts, and drinking my coffee, slowly.

Dedication

A Letter To the Man Who Taught Me to Fold My Shirts

There was once a man I knew, years ago, who changed his name for a poet. Not for fashion, nor fame, but because he believed a life should take the shape of its highest devotion. He wore Italian suits like second skin, spoke with such undelaying eloquence that silence felt impolite in his presence, and moved with the poised precision only ritual can grant. He never explained himself. He didn’t need to. Even as a twelve-year-old, I understood that his presence alone taught more than most syllabi: that poise could be an ethic. That how one dressed, how one entered a room, how one addressed the world — could be philosophy, far removed from footnotes.

He was never loud, never theatrical. He taught literature while pursuing his PhD, but more than that — he made beauty feel liveable. He made it feel like something you could aspire to, not for applause, but for alignment. I remember once disappointing him — and the shame I felt was unbearable. Not because he scolded me, but because he didn’t. His silence made the standard clear: dignity is not enforced. It is expected. And from that day onward, I found myself imitating him — the way he walked, the way he paused before speaking, the way he greeted others like being alive was something to revere, not fear. I even chose my university to follow in his footsteps — though he does not know this.

We spoke, once, about attention, and my so-called learning difficulties. And in that quiet exchange, I realised he saw me — not as a problem to be managed, but as a mind in the making. He never claimed to be a philosopher. But in the truest sense, he was the first I ever met. Not a philosopher of concepts or systems — but of form, of presence, of lived ethos.

I still press my shirts the way he did. I wear tailored suits in the hope that I might carry the same kind of elegance. I still believe that rhythm is a way of honouring thought. And though he will not appear in the bibliographies or citations that follow — this entire essay stands in his silhouette.

It is for him.

And whatever pursuit of reason I have embarked on — it begins with him.

Bibliography

Benjamin, W., 2008. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media. Harvard University Press.

Borgmann, A., 1984. Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life: A Philosophical Inquiry. University of Chicago Press.

Byung-Chul Han, 2020. The Disappearance of Ritual: A Topology of the Present. Polity Press.

Camus, A., 1951. The Rebel: An Essay on Man in Revolt. Translated by A. Bower. Vintage International.

Camus, A., 1991. The Myth of Sisyphus. Translated by J. O’Brien. Penguin Books. (Original work published 1942)

Confucius, 1998. The Analects. Translated by D.C. Lau. Penguin Classics.

Heidegger, M., 1971. ‘...Poetically Man Dwells…’, in Poetry, Language, Thought. Translated by A. Hofstadter. Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Merleau-Ponty, M., 2012. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by D.A. Landes. Routledge. (Original work published 1945)

Nietzsche, F., 1999. The Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings. Edited by R. Geuss and R. Speirs. Translated by R. Speirs. Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1872)

Nietzsche, F., 1974. The Gay Science. Translated by W. Kaufmann. Vintage Books. (Original work published 1882)

Plato, 1999. Symposium. Translated by A. Nehamas and P. Woodruff. Hackett Publishing. (Original work c. 385–370 BCE)

St. Augustine, 2008. Confessions. Translated by H. Chadwick. Oxford University Press. (Original work c. 397–400 CE)

Wittgenstein, L., 1922. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Translated by C.K. Ogden. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

World Health Organization, 2017. Obesity and Overweight – Fact Sheet. [online] Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight [Accessed DD Month YYYY].