Why Aristotle Said Pleasure, Honour, and Wealth Will Never Make you Happy.

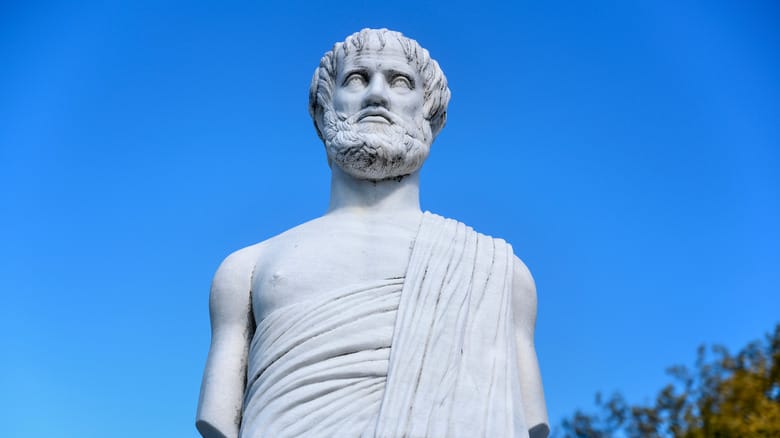

What makes life truly worth living? Ancient philosophers debated whether happiness lies in pleasure, wealth, honour — or something deeper. In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle offers a radical answer: the good life is not about indulgence or status, but the pursuit of rational virtue across a lifetime.

This essay explores Aristotle’s arguments against popular views of happiness, supported by historical examples — from tyrants to philosophers — and challenges his assumptions through later thinkers like Epicurus.

In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle seeks to define the purpose of human life. He concludes that it lies in achieving eudaimonia, best understood not as fleeting happiness but as flourishing — a sustained condition marked by rational activity and virtue. To get there, Aristotle critiques three common conceptions of happiness: pleasure, honour, and wealth. Each, he argues, fails to meet the criteria of self-sufficiency, permanence, and alignment with reason and virtue.

Aristotle distinguishes two types of virtue: moral and intellectual. Moral virtues — such as courage, temperance, and justice — regulate desire and emotion in accordance with reason. Intellectual virtues, like phronesis (practical wisdom) and sophia (theoretical wisdom), involve understanding how to act well and grasp eternal truths. Eudaimonia, he argues, is possible only through the integration of both types of virtue (NE II, 1103a15–1109b30; VI, 1139a15–1145a15).

This ethical vision is deeply tied to Aristotle’s political philosophy. In Politics, he describes the polis — the self-sufficient city — as the natural setting in which rational flourishing can occur (Politics 1.2, 1252a–1253a). Humans are "political animals," and true happiness is found not in isolation, but in civic life. Aristotle places great emphasis on civic friendship — bonds of mutual goodwill formed through shared participation in public affairs (NE VIII.9, 1159b25–1160a6).

In Book I of Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle critiques pleasure as the lowest form of life — calling it "slavish" and fit for beasts (NE I, 1095b20). Pleasure is transient, bodily, and irrational. It cannot provide the permanence or intellectual depth needed for eudaimonia (NE I, 1095b14–1096a10). Prioritising pleasure undermines the moral development and rational growth necessary for individual and civic flourishing.

Greek history supports this critique. Dionysius II of Syracuse, infamous for his indulgence, failed to reform under the influence of Plato and Dion and remained a tyrant (Plutarch, Life of Dion). His descent reflects both Plato’s and Aristotle’s fears about the corrupting force of hedonism (Republic 545c–547a; NE 1095b14–1173a14). While Aristotle later nuances his view — distinguishing between base and higher pleasures (NE X, 1172b27–1173a21) — he never wavers from the view that pleasure alone cannot sustain a rational, virtuous life.

Later thinkers like Epicurus challenged this. In his Letter to Menoeceus, Epicurus defined pleasure not as indulgence, but as ataraxia — freedom from pain and anxiety (129–132). He upheld rationality and moderation, making a compelling case that thoughtful, restrained pleasure could be the highest good. Unlike Aristotle, Epicurus critiques the anxiety provoked by striving for virtue, arguing that peace of mind is more achievable. While Aristotle’s dismissal of pleasure remains powerful, Epicurus exposes its lack of nuance. Intellectual pleasure, in moderation, may well complement a flourishing life.

Aristotle also critiques honour for its dependence on others. You cannot be honourable without being recognised as such — making honour inherently unstable (NE I, 1095b22–1096a5). In Politics, he warns that leaders driven by the pursuit of honour often become demagogues (Politics 5.11, 1310a25–30), manipulating public opinion and destabilising the city-state (Politics 4.11, 1295b1–5).

The Athenian demagogue Cleon, who called for brutal retaliation during the Mytilenean revolt, illustrates this. His pathos-laden rhetoric stirred the people into nearly committing mass execution (Thucydides 3.36–38). Aristotle’s critique fits. Yet contrast Cleon with Pericles, who used his popularity to promote democracy, fund the Parthenon, and unite Athens (Thucydides 2.34–2.46). Honour can corrupt — or inspire civic greatness. Aristotle’s critique lacks the nuance to distinguish between these outcomes.

Still, honour fails his criteria. It depends on the fickle judgment of others, and its pursuit can foster tyranny or distraction. While Pericles used honour virtuously, his exception proves the rule. Honour is insufficient, and Aristotle’s scepticism remains valid.

Aristotle’s rejection of wealth is clearer. He sees wealth as merely instrumental — useful only for other ends, never good in itself (NE I, 1096a5–15). Pursuing wealth as an end breeds greed and undermines civic unity. In Politics, he warns that economic inequality destabilises society, divides citizens, and threatens the polis (Politics II.7, 1256b30–1257a5).

Herodotus’ tale of Croesus, King of Lydia, captures this. Despite his immense fortune, Croesus sought Solon’s confirmation of his happiness — only to be told that true happiness could only be judged at life’s end (Histories 1.30–33). Croesus’ downfall supports Aristotle’s claim: wealth is impermanent and insufficient for flourishing. Wealth-centric Greek cities, like oligarchic Corinth, also suffered from unrest due to inequality (Thucydides I.13).

In conclusion, Aristotle rejects pleasure, honour, and wealth as foundations for the good life. Each fails to meet his criteria of self-sufficiency, permanence, and virtue. His political writings reinforce this, showing how these pursuits also destabilise the city-state. Though his critiques occasionally lack nuance — particularly concerning pleasure and honour — his broader vision of eudaimonia through rational, virtuous living remains a profound and enduring contribution to ethical and political thought.

Bibliography

- Aristotle (2009) Nicomachean Ethics. Trans. D. Ross, rev. L. Brown. Oxford University Press.

- Aristotle (2013) Politics. Trans. C. Lord. 2nd ed. University of Chicago Press.

- Epicurus (2012) The Art of Happiness. Trans. G. Strodach. Penguin Books.

- Herodotus (2003) The Histories. Trans. R. Waterfield. Oxford University Press.

- Plato (2007) The Republic. Trans. D. Lee. 2nd ed. Penguin Classics.

- Plutarch (1973) Life of Dion, in The Rise and Fall of Athens: Nine Greek Lives. Trans. I. Scott-Kilvert. Penguin Books, pp. 185–212.

- Thucydides (1998) History of the Peloponnesian War. Trans. R. Warner. Penguin Classics.