Why Evolution May Have Killed Moral Truth: The Case Against Moral Realism

What if our deepest moral instincts aren't about truth at all—just survival?

This essay explores a haunting question at the intersection of evolution and ethics: If natural selection shaped our moral beliefs, should we trust them? Moral realism, the idea that there are universal moral truths independent of human opinions or culture, depends on our ability to "track" those truths. But what if we evolved not to see what's true, but just to stay alive?

Drawing on the work of Sharon Street, Guy Kahane, Richard Joyce, and David Enoch, this piece walks through the philosophical debate known as the "Darwinian Dilemma." Along the way, it examines whether evolution helps explain morality—or if it quietly destroys our reason to believe in moral truth at all.

1. Introduction

If our moral beliefs are shaped by evolutionary pressures rather than truth-tracking processes, this raises a profound question: Can we still trust them? This tension strikes at the heart of moral realism, which claims that moral beliefs must track stance-independent truths. Sharon Street formalised this problem. I argue that evolutionary forces undermine the epistemic foundation of moral realism, making anti-realism a more epistemically secure account. This analysis begins with Street's Darwinian Dilemma.

2. Conceptual Foundations: Realism, Anti-Realism, and Truth-Tracking

To address whether evolutionary explanations undermine moral belief, we must define key terms. Moral realism posits stance-independent truths—facts valid regardless of reason, culture, or perspective. Anti-realism, by contrast, denies such truths, holding that moral beliefs are shaped by social, emotional, or practical concerns.

Constructivists like Korsgaard (1996) argue that morality is built through rational procedure, not discovered as objective fact. Crucially, if evolution undermines truth-tracking, then realism collapses. Evolutionary explanations pose a unique threat to realism, not to modern morality as a whole. Anti-realist and constructivist views do not rely on the assumption that moral beliefs track truth.

Throughout this essay, the focus remains on realism because it alone bears the epistemic burden that evolution calls into question. Anti-realism avoids the implausible task of justifying evolved beliefs as stance-independent truths. If our moral beliefs evolved primarily for pragmatic survival, not for truth or justice, we have strong reason to doubt their validity.

3. Street's Darwinian Dilemma: An Evolutionary Challenge to Realism

Sharon Street's Darwinian Dilemma shows that if evolution shaped our moral beliefs for survival, realism faces an epistemic crisis: Either evolution did not track truth, or it did.

The first horn of the dilemma accepts that evolution shaped our moral beliefs but denies any necessary link between those beliefs and objective truths. This view maintains that stance-independent moral facts exist, but our evolved beliefs don’t reliably track them. But this forces the realist into an uncomfortable position: Why should we trust survival-driven beliefs to reveal moral truth?

As Street argues (2006), if our beliefs were selected for fitness rather than truth, then we have no reason to think they are true. This pushes realism into moral scepticism.

The second horn holds that evolution did track moral truths—that organisms survived because their beliefs aligned with objective morality. But Street identifies three major flaws in this position:

- Lack of Parsimony: It invokes both moral truth and evolutionary selection when only one is needed. Anti-realism offers a simpler explanation.

- Lack of Clarity: Why would tracking moral truth help survival more than useful fictions?

- Lack of Explanatory Power: It cannot explain why evolution selected specific moral beliefs.

Street concludes that realism fails under evolutionary scrutiny. Neither horn escapes debunking.

4. Strengthening the Argument: Kahane and Joyce on Epistemic Defeat

Guy Kahane (2011) formalises the logic of evolutionary debunking arguments (EDAs):

- Causal Premise: Our moral beliefs were shaped by evolution.

- Epistemic Premise: Evolution aims at survival, not truth.

- Conclusion: Our moral beliefs lack epistemic justification.

Kahane notes that not all causal origins undermine belief—only those that disconnect belief from truth. Evolutionary origins only justify belief if we have independent reason to think those beliefs are true. But because evolution favours survival, not truth, that justification is absent.

Kahane stresses that this is not a genetic fallacy. If the origin of a belief is systematically off-track, and we lack other justification, the belief is unreliable. Even reflective reasoning could be shaped by evolution, making post-hoc rationalisations suspect.

Internal coherence is no rescue either. A set of beliefs may be coherent and false if built on non-truth-tracking foundations.

Richard Joyce deepens the critique. He emphasises that moral beliefs differ from scientific or mathematical ones. Science has feedback loops to correct falsehoods; morality does not. Evolution favoured behavioural outcomes—cooperation, reproduction—not truth.

Joyce illustrates this with a tribal belief: that a river god punishes liars with illness. The belief isn't true, but it deters dishonesty, benefiting survival. Evolution doesn't care about truth. It cares about fitness. Survival, not truth, is the filter. And that erodes trust in our evolved moral intuitions.

Both Kahane and Joyce converge: without independent justification, realism cannot survive evolutionary critique.

5. Enoch’s Third Factor Response: A Last Stand for Realism?

David Enoch attempts to rescue realism with a "third factor" solution. He suggests that evolution did not track moral truths directly, but tracked survival, which happens to correlate with moral truth.

Enoch avoids claiming evolution was truth-sensitive. Instead, he argues for a non-causal harmony: survival is morally good, and evolution selected for survival, so moral truths were indirectly preserved.

But this harmony is fragile. It assumes survival just happens to align with truth—a coincidence that contradicts what we know about evolution. False but adaptive beliefs (e.g., tribal gods) are common.

Enoch’s account relies on an unproven link between truth and fitness. Even if survival occasionally aligns with moral truth, there's no guarantee across moral domains. The biblical story of Cain and Abel may teach peace, but there's no evidence it tracks metaphysical reality.

Ultimately, Enoch's defence does not offer strong enough justification to restore realism’s credibility.

6. Conclusion

Evolutionary explanations undermine the epistemic justification for moral realism. Realism depends on access to stance-independent moral truths. Street's dilemma, Kahane's formalisation, Joyce's evolutionary analysis, and the weakness of Enoch’s third-factor defence all point to the same conclusion: we cannot trust evolved moral beliefs to reflect objective truth.

Anti-realism, by contrast, avoids these epistemic pitfalls. If moral beliefs are survival tools, not truth-trackers, realism loses its foundation.

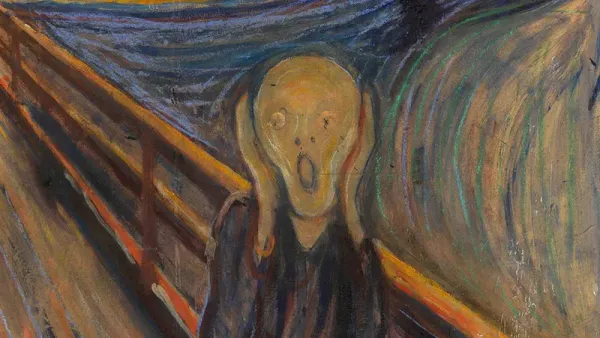

Morality may feel universal. It may feel sacred. But if evolution is the author of our intuitions, then those feelings may be no more reliable than the instincts of a gazelle.

Bibliography

Enoch, D. (2010) ‘The epistemological challenge to metanormative realism: How best to understand it, and how to cope with it’, Philosophical Studies, 148(3), pp. 413–438.

Joyce, R. (2006) The Evolution of Morality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kahane, G. (2011) ‘Evolutionary debunking arguments’, Noûs, 45(1), pp. 103–125.

Korsgaard, C.M. (1996) The Sources of Normativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shafer-Landau, R. (2003) Moral Realism: A Defence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Street, S. (2006) ‘A Darwinian dilemma for moral realism’, Philosophical Studies, 127(1), pp. 109–166.