Why We Shouldn't Fear Death: Lucretius, Poetics, and the Epicurean Pursuit of Peace.

What if death meant absolutely nothing to you — not because you were in denial, but because it simply didn’t matter?

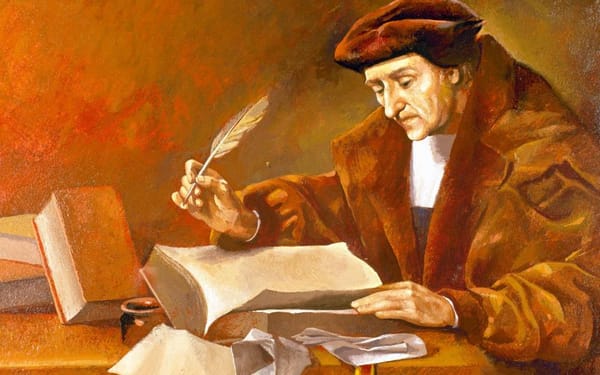

That’s the radical claim of the Roman poet-philosopher Lucretius in On the Nature of Things. Rooted in the Epicurean tradition, Lucretius presents a materialist vision of the soul and argues that death, being the end of sensation, cannot harm us. In an age still obsessed with legacy, heaven, and the fear of the unknown, his thinking remains both strange and freeing.

This piece explores how Lucretius builds his case — through natural philosophy, poetic analogies, and the now-famous “symmetry argument.” We’ll also examine how modern thinkers like Thomas Nagel challenge his view, and whether Lucretius' ideas still hold up in the face of existential dread.

1. Introduction

Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things is both a philosophical and poetic defense of the Epicurean lifestyle, with Book 3 aiming to dispel humanity’s fear of death and guide us toward the ideal of ataraxia — a state of serene peace. He explores the material nature of the soul and its unity with the body, arguing that death, as the cessation of sensation, is ultimately insignificant and should not be feared.

This essay analyzes how Lucretius’ materialist stance supports the Epicurean goal of ataraxia. Central to his argument is the “symmetry argument,” which posits that death mirrors pre-birth non-existence. By showing that neither involves sensation or harm, Lucretius hopes to dissolve our fear and affirm death’s irrelevance.

2. The Material Nature of the Soul

Lucretius uses natural philosophy to justify Epicurean beliefs. In Book 3, he argues for the unity of mind and body and defines death as the simultaneous cessation of both. To support this, he outlines a fully materialist theory of the soul.

Unlike Platonic dualism — in which the soul is immaterial and immortal — Lucretius contends that the soul is composed of fine, light atoms. Writing in poetic form, he compares it to wine and perfume (III.220–230): substances that evaporate without leaving visible traces. Likewise, the soul disperses at death, leaving the body intact but devoid of sensation and life (III.455–470, 830–850).

Lucretius elaborates further with a theory of four atomic elements: heat, air, wind, and a subtle, unnamed fourth element. These combine to enable sensation and consciousness (III.455–470). As O’Keefe explains in Epicureanism, heat provides vitality, air and wind enable motion, and the unnamed fourth element — extremely fine and mobile — is crucial for sensory responsiveness (O’Keefe, 2010, p. 62).

However, this part of the theory ventures into speculative territory. While the analogy to perfume feels grounded in observation, the four-element theory lacks empirical backing. This raises doubts about how fully materialist or empirical Lucretius’ account really is — potentially undermining his claim that his view of death is based entirely on observable phenomena.

Still, Lucretius maintains that sensation arises from interactions between soul atoms and bodily atoms, reinforcing the unity of soul and body. This materialist stance directly opposes Plato’s metaphysical reasoning in the Phaedo (78b–80b). Where Plato sees the soul as eternal, Lucretius grounds it in physics.

Because the soul is finite and dies with the body, Lucretius argues that there can be no postmortem experience — and thus no postmortem suffering. This, in turn, supports ataraxia by removing the fear of a painful afterlife.

3. Rejection of Immortality and the Fear of Death

Lucretius holds that, since the soul and body are unified and both cease at death, death cannot affect us. This aligns with core Epicurean doctrine. As Epicurus famously writes in Letter to Menoeceus, “Death is nothing to us, since every good and every evil lies in sensation; but death is the privation of sensation” (Epicurus, 2012).

While Lucretius builds on this idea with poetic analogies and atomic theory, his conclusions mirror Epicurus' original premise: once sensation ends, nothing remains to be feared.

This view starkly contrasts with other Hellenistic philosophies. The Stoics, for example, accepted some kind of survival after death. Marcus Aurelius, often cited as a Stoic figurehead, reflects on this in Meditations: “If souls survive, how does the air contain them all from eternity?” (Meditations, 4.21). Even though he questions the plausibility of soul survival, his cosmological framing — of souls reintegrated into universal reason — contrasts sharply with Lucretius’ purely materialist, empiricist approach.

Interestingly, Marcus also offers a practical detachment from death: “a release from bodily and mental disturbances” (Meditations, 12.7). Though less empirical, this emotional stance parallels Epicurean ataraxia. Both philosophies aim to neutralize death’s terror, but only Lucretius bases his view in physical observation and analogy.

4. The Symmetry Argument

Lucretius’ symmetry argument claims that death and pre-birth non-existence are the same — and thus equally unthreatening. Since we do not fear the void before birth, we should not fear returning to it (III.850–860). He compares life to a temporary lease rather than permanent ownership (III.971–979). This reinforces ataraxia by showing that death, being identical to harmless pre-birth nothingness, is not worth fearing.

Philosopher Thomas Nagel directly challenges this view in Mortal Questions. He argues that death can harm us by depriving us of possible future goods — even if we are not conscious of this deprivation. He uses the analogy of brain injury: losing cognitive abilities is harmful, even if the person cannot perceive the loss (Nagel, 1979, pp. 6–7).

Nagel also critiques the symmetry claim itself. Pre-birth non-existence deprives us of nothing, while death ends a life in progress. This “temporal asymmetry” means the two states are not identical (pp. 7–8).

Lucretius might reply that such deprivation is irrelevant to the dead. Without sensation, there can be no loss or harm. The Epicurean focus remains firmly on the living subject’s peace of mind — not on metaphysical speculation about what could have been.

The symmetry argument can be formalized as:

- Premise 1: Pre-birth and post-death non-existence are identical states.

- Premise 2: Pre-birth non-existence causes no harm or fear.

- Conclusion: Post-death non-existence should also cause no harm or fear.

The logic is valid, but only persuasive if one accepts Premise 1 — the equivalence of the two non-existences. For those who see death as an active loss of lived potential, the argument may fail to resonate emotionally, even if it remains coherent within Epicureanism.

Still, Lucretius' response is clear: concern about postmortem experience is meaningless, because there is no subject left to experience it. Within his framework, death is quite literally nothing.

5. Conclusion

Lucretius’ materialist view ties soul and body together, arguing that their simultaneous dissolution at death leads to the cessation of sensation — and thus, no suffering. This supports the Epicurean ideal of ataraxia: the untroubled mind.

His symmetry argument, though challenged by modern thinkers like Nagel, remains a powerful example of rational detachment from fear. While it may not soothe everyone — especially those who see death as an active deprivation — it coherently reflects Epicurean principles and offers a bold alternative to traditional views on mortality.

For those who can embrace his framework, Lucretius offers more than just comfort. He offers a path to peace.

Bibliography

Ancient Texts

- Aurelius, M. (2006). Meditations. Trans. Martin Hammond. Oxford World Classics.

- Epicurus. (2012). Letter to Menoeceus. In The Art of Happiness, trans. George K. Strodach. Penguin Books.

- Lucretius. (2001). On The Nature of Things. Trans. M.F. Smith. Hackett Publishing.

Modern Texts

- Nagel, T. (1979). Mortal Questions. Cambridge University Press.

- O’Keefe, T. (2010). Epicureanism. Acumen Publishing.